Nova Scotia’s Ancient Drumlin Hills Furnish Ideal Landscape for Simple, Silent Architecture

By Martha Breen, June 28, 2016

When the first Scottish settlers landed on the eastern coast of the New World, the terrain so reminded them of their home — with its glacier-rolled drumlin hills and steep valleys thick with fir, spruce and pine; wild, ragged cliffs; the restless, jadeite-coloured ocean — that they, understandably, named it New Scotland.

Mapmakers, of course, soon Latinized the name. But four centuries on, people arrive at the crests of the drumlins, usually in cars now instead of ships, and are still startled by the vast, wide-open vistas that typify the landscape of Nova Scotia.

When the owners of this property, both Ontario expats, first approached Halifax architect Brian MacKay-Lyons, of MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects, to help build their retirement dream home in Lunenburg County on the South Shore, the choice of property played a leading role in both the concept and execution of the project.

Architecture in a place like this, MacKay-Lyons believes, should take its cues from the topography; it’s part of a kind of stewardship, or respect, for what nature has already made.

“Our designs are very inspired by the idea of landscape in general,” says MacKay-Lyons, who himself owns a farm in Upper Kingsburg, not far from here. “In our firm, we feel it’s important to pay attention and respect the landscape. This is true worldwide, not just here; I feel we’ve forgotten how to do that as a society.”

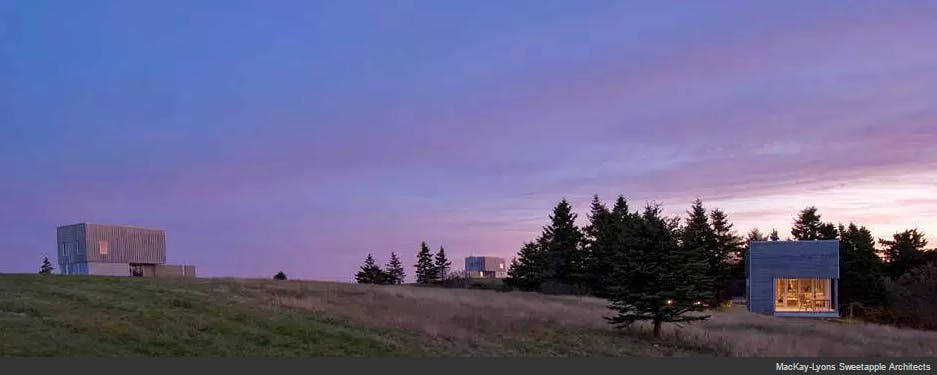

In a stroke of luck, the clients had engaged him before making a final decision on the piece of land they would buy; when they asked his opinion on a pair of adjacent properties, each with its own high drumlin hill, he convinced them to buy both, and built “twins” — two virtually identical hilltop houses facing each other, separated by a marshy valley. One is the main house for the couple and overlooks the estuary of a nearby river; the other is a guest house that faces outwards, towards the ocean. While minimalist and modern, they feature rustic rough-sawn hemlock board-and-batten, and very simple, geometric forms; they’re meant to be seen from afar. “The houses were inspired by Lunenburg County barns, which are always sited on hilltops, because that’s where the best farmland is,” he says.

A couple of years later, the couple returned to ask him for a third structure: a separate pavilion for a sauna/spa and exercise room that could double as additional guest space. “We wanted it to be independent of the house,” one of the homeowners explains, “because we wanted to maintain our house as a living space. We wanted [this] to be calming and elegant in its simplicity; a site that you could walk through the trees to get to, and you wouldn’t even be aware of till you got there.”

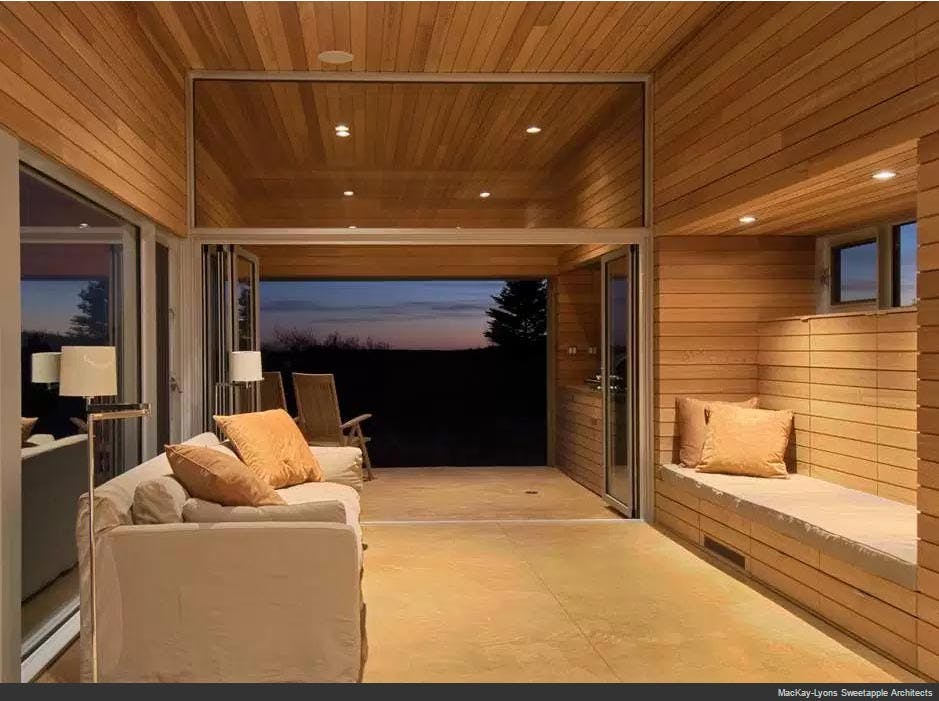

The commission presented MacKay-Lyons and his team with an opportunity to contrast the open, expansive design of the twin main houses, with a series of opposing yet complementary ideas. While the two larger houses sat on the crests of hills with huge views of sky and water around them, the new building would sit in the valley between them, nestled in a marshy wood. In contrast to the expansive proportions of the larger structures, it would be small and intimate, with enclosed, secret spaces, cozy places to curl up with a book, and humane proportions. It would also look softer: instead of rough-sawn hemlock, the entire spa would be clad inside and out in resawn clear cedar shiplap, smooth on bare skin (desirable in a sauna, of course) and soothing to the eye. Even the concrete floor would be tinted the same honey-yellow tone as the wood.

In contrast to the open terrain surrounding the main and guest houses, which are joined by a wooden bridge spanning the valley between them, the approach to the spa leads over a wooden walkway through the woods, transecting a cultivated wildlife corridor frequented by deer and foxes. Going to the spa is a figurative as well as literal journey — or as MacKay-Lyons puts it, a form of choreography of close-up and wide-angle views, consciously managed.

“The geometric relationships of all three buildings are very precise, so that in a sense, it doesn’t feel like three separate buildings at all,” he says. “It almost as if it’s one cohesive building with different sections, that you reach through open-air hallways, which are the wooden walkways. It’s a bit like the principle in judo, of using the energy of the other person.”

In shape and colour, as MacKay-Lyons describes it, the spa is “like a block of butter.” A covered porch cuts a square out of the near corner; you enter through a transparent doorway to a small anteroom with a built-in daybed. This is one of several perches in the house, great for stretching out for a siesta or gazing out into the landscape.

It’s a prelude to the view that awaits around the corner, where the interior opens into a single airy space. On one side is a built-in kitchenette and another daybed balancing the one at the entrance; on the other, a long bank of windows framing a vista of trees and rolling meadow — and beyond that, ocean, under an impossibly big sky.

One of the subtler pleasures of the design is that, despite its high ceilings, an imaginary beltline at the eight-foot level is acknowledged in various ways all around the perimeter. It forms the top of the alcove sheltering a built-in daybed on the far side, wall-to-wall glass transoms at each end of the main room, and the line where the top of the long-side windows meets cedar upper wall. This strong horizontal line adds human scale and strengthens the mood of relaxed intimacy.

The space ends on the other side in another covered porch, segregated from the interior by a NanaWall (a series of hinged glass doors that fold, accordion-style, out of the way), that opens the room to the ocean breeze. (A motorized screen on the outer side keeps out bugs, perhaps a less romantic aspect of the nearby marsh.)

According to MacKay-Lyons, “I really feel if you handle the ‘choreography’ of the building well — controlling the sequence of intimate and open spaces, the idea of withholding and then revealing views — then the overall design itself can be very simple.

“That’s an important part, I feel, of the idea of stewardship over the landscape. I like to make buildings that are more silent, but have more to say.”

Original Article: National Post